Queers carry around collections of resonant words, or I suspect many of us do. Like pebbles in a pouch.

Among these, the broadest distinction is between words that describe ourselves, words we use to describe the world, and words we use to speak of God or the transcendent, if at all. (I am creating a typology extemporaneously, so, in what follows, when a sentence doesn’t include a hedging I think, maybe, or possibly, assume it’s implied.)

Words that describe ourselves clarify, to varying extents, the people we experience ourselves to be, the people we perceive others perceiving us to be, and the shifting mediations between those more internal and more external perceptions, the overlaps and gaps that we experience in moments of euphoria and dysphoria.

One category of resonant self words demarcate kind, genre, identity, gender. Among these kind words, some have already congealed—or been pressed, like tofu—into firm identities, i.e., names establishing that I am to be properly understood in relation to certain others who share certain characteristics, a temperament, an aesthetic. Other kind words are more personal words that are less useful in explaining who I am in relation to other people and more useful for explaining who I am in relation to who I have been and who I am before God. Kinds can be self-elected, chosen by others, or arbitrarily but inexplicably persistent. Whatever the case, the only ones that matter here are the ones that resonate for how they precisely name or precisely misname or both at once—for how they bless or wound.

Some of my own resonant kind words—simple, kenning, compound: gay man, faggot, sodomite, brother, guncle, dogfather, clown, Bride of Christ, child of the heavenly Father.

Other resonant words speak less to specific kinds of queer persons and more to specific textures or states of queer being. The most common examples of texture are probably hard and soft. Butch and femme begin as textures and quickly become kinds or genders, so they have one foot here and one foot there.

Textures can be ways of adopting, transforming, or forgetting entirely the binary categories of male and female and their gay cousins masculine and feminine. The states of being words name qualities that are harder to nail down, slipping, as they do, away from totalizing pneumonic binaries. It’s hard to think of examples. Anxious comes to mind.

Some of my resonant textures and states, which continue to crop up in my writing: soft, full.

The words we use to speak of God (“describe” sounds too flat, like a quick pencil sketch where one wants a battery of organs) are intimate and always at risk of becoming cliché. I will not say more about them now or share mine here. Besides the names I have inherited—many of which still resonate—I think I may only have one.

And the words we use to describe the world… I’ve been thinking about words because I have been reading the first two books by Aurora Mattia, and to read her books is to have a rare experience of a kind I love: walking through another queer’s world through their developed and idiosyncratic language, through encountering their carefully chosen and lovingly honed resonant words.

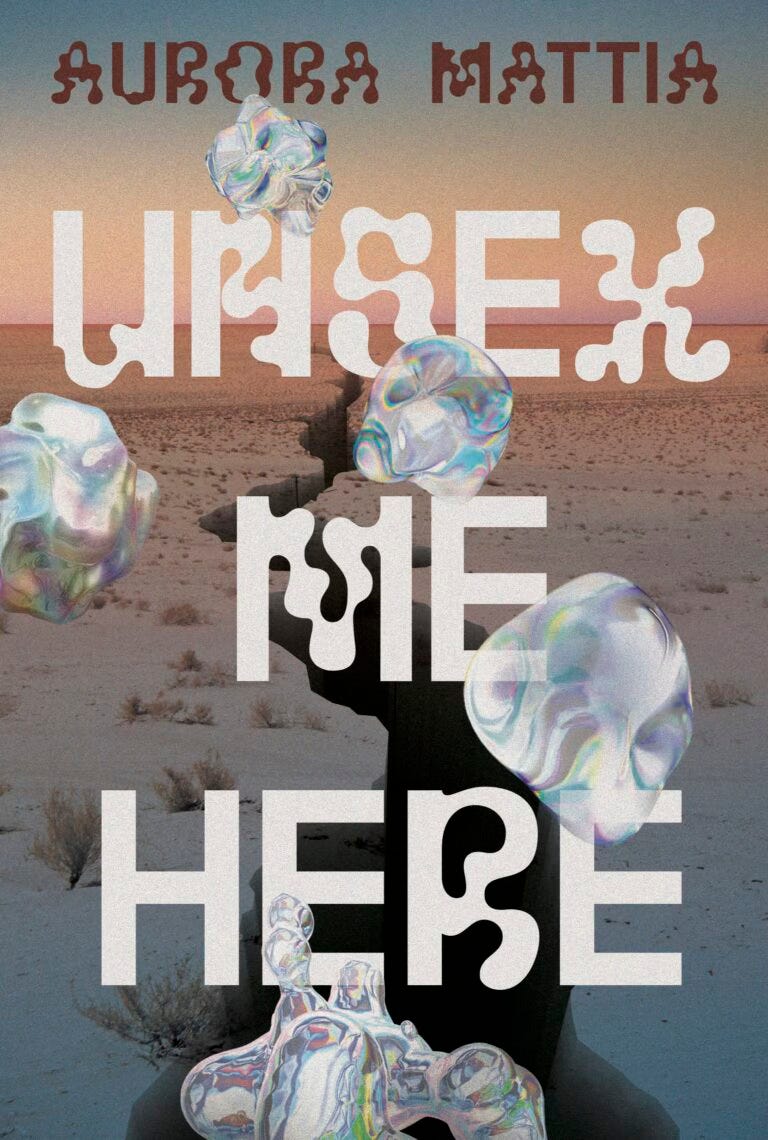

Mattia’s first book is The Fifth Wound, a mystical queer novel published in 2023. Her second book is Unsex Me Here, a collection of shorter visions and revisions. I started reading The Fifth Wound in 2023 but couldn’t get far. I started a few times, actually. Liz, the friend and bookseller who recommended it to me, said that the first pages were difficult but that the book was unlike any other, and she was right on both counts. Only after killing my Instagram, X, and Facebook accounts a few months back (like the protagonist of “Madonna Della Nulla” in Unsex Me Here) and getting some of my attention back could I read sentences slowly enough and with enough focus that I could follow the twists and transformations that Mattia’s sentences take.

The narrator of The Fifth Wound is Aurora, a fairy cum woman, who counts her wounds: surgery scars and a stabbing wound on her face, courtesy of a stranger on the subway. Mattia is steeped in mystical theology and some of Christianity’s more arcane voices, so if counting wounds sounds Christic or stigmatic, it is.

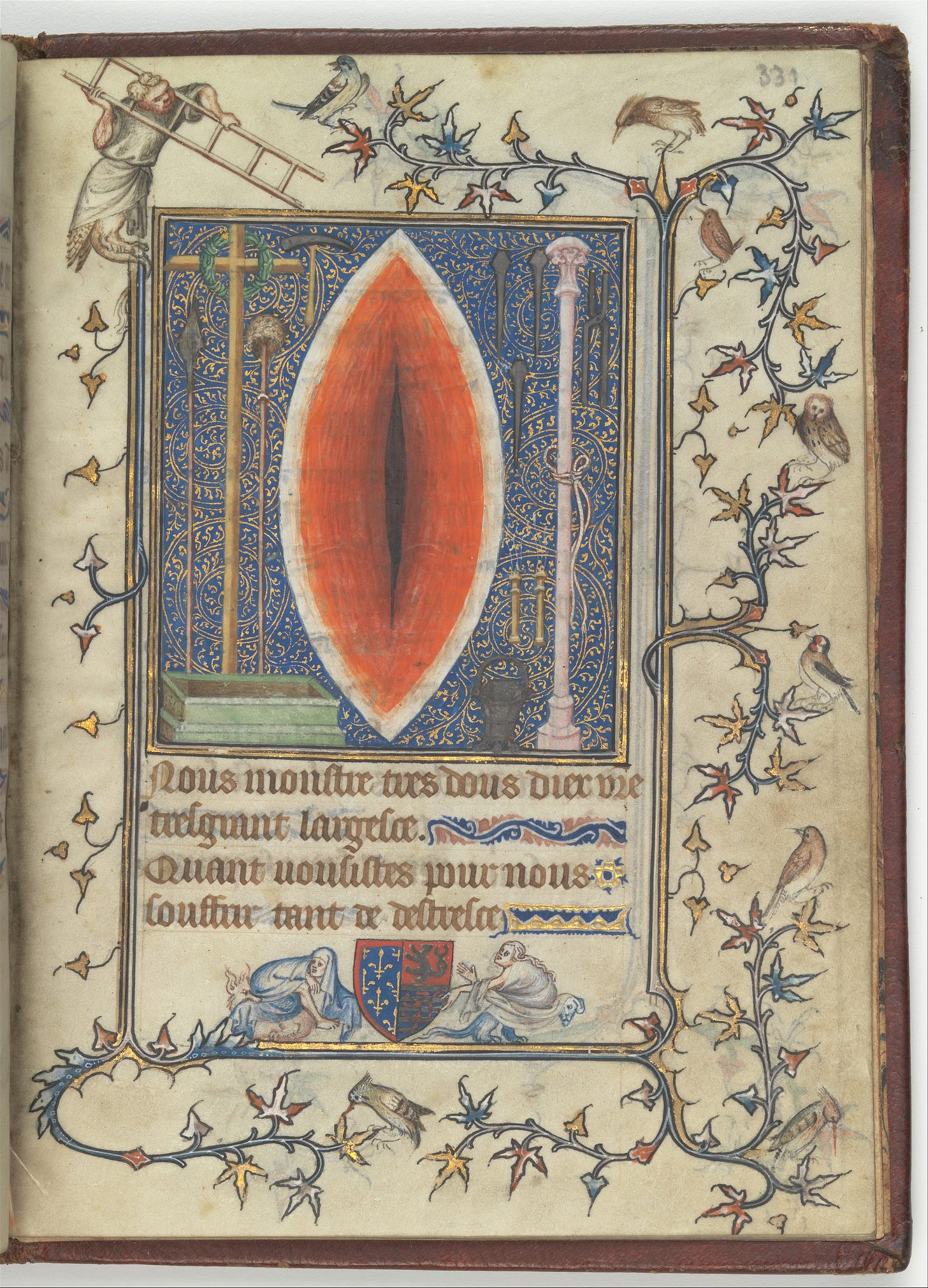

In treating her speaker’s wounds as sources of spiritual inspiration, Mattia joins a lineage of mystics. Some medieval Christians read the side wound of Christ—the cut on the crucified’s torso where the Roman soldier punctured his skin with a spear, causing water and blood to flow out—as the womb from which Christ births the church. Christ is, in this image, mother. Accordingly, illuminated Bibles portrayed the side wound as a vagina. Mattia includes one such illustration in her book.

In the introduction to Glorious Bodies: Trans Theology and Renaissance Literature (2024), Colby Gordon surveys readings of George Herbert’s poem “Bag,” in which Christ invites the faithful to slip prayers and messages into his side wound, as he doesn’t have a bag. Scholars have read the side wound in the poem as a vagina or a scrotum, determining that the wound as vagina makes Christ a woman or as scrotum makes Christ a man. In both cases, the wound is read as unambiguous genitalia that is determinative of binary gender. These preclude trans readings of the crucified body. Gordon writes, “An invaginated man at the center of a brutal, homoerotic scene of ‘all-male’ violence, but also a pregnant mother with a swollen penis, the crucified Christ serves as a rich repository for both tansmasculine and transfeminine possibilities.” Jesus was killed by an empire, the Roman empire, so these trans readings bear an uncomfortable proximity to state violence. Gordon continues, “That these trans potentials emerge as part of a scene of eroticized violence—as part of an execution—ominously looks forward to the transphobic futures of state violence.”

Christian devotion to Jesus’s side wound foreshadows the opposite, perverted attention of transphobes who train their sights obsessively on trans people’s bodies and the practices that transform them. Fundamentalism encourages Christians to bludgeon Scripture’s multi-genred textual body and polymorphous Good News with the bluntest of “literal” readings (while ancient monks, through lives spent reading the Bible like breathing air, developed numerous kinds of spiritual readings). Christians have generated a similarly crude approach to gender, imposing “literal” dimorphic categories on the vastly variable human body. The fundamentalist’s reduction of the Bible to surface prooftexts is of a piece with the transphobic Christian’s reduction of the human body to two genders dependent on two discreet kinds of sexual organs. Both are misreadings that further dull the senses.

At this cursed moment, the loudest discourses about trans people are, at best, medicalized language aimed at the hopeful procuring of health care and educational rights, and at worst, nationalist rage aimed at making life unlivable for trans people on all fronts. While not equivalent, these are two sides of the same crumbling cookie. The latter is genocidal (this is a considered use of the word). The former is the best that exists within the current system and still linguistically and imaginatively stultifying. We need devotion to trans bodies and literatures to teach us how to speak. (If Mark D. Jordan hasn’t written that exact sentence, he’s written a very similar one, so consider this a partial citation.)

The Fifth Wound and Unsex Me Here are the fruit of a writer who understands the dynamics of devotion. In “Madonna Della Nulla,” Mattia writes, “The details were many but the desire was simple. Details happen when desire, like light, is shredded by the colorful sawteeth of a kaleidoscope. . . . Details make a revelation of happenstance.” Devotion exuberates, deepens understanding, fills, overflows, and multiplies meanings in the service of that which is beyond language and human understanding; perverted devotion flattens, reducing the ineffable to an idol.

Attention to the author’s own body and mind, and to those of her lovers, allows her to speak freely about people as things besides “women,” “men,” “cis lesbians,” and “cis gay boys.” These names not only fail but are slip covers for repression and confusion—forms that Empire promises will bring salvation through inclusion while delivering its opposite. Aurora’s lovers are, rather, fairies and nymphs whose practices of embodiment are as in flux as hers is. A fairy she loves sees something of himself in her, tries on her lipstick and feels beautiful. Sometimes, meeting a tgirl, I feel suddenly bashful, newly aware and proud of my own humbler effeminacies that vibrate in her presence. I don’t think I’d read anything that speaks to this prior to The Fifth Wound.

Mattia’s sentences expand and expand, with entirely new thoughts or memories opening up where one might expect a comma or period. Her diction is prismatic and her sentences can be wildly associative and dissociative at the same time: a thought occurs that follows from the last, but suddenly we’ve slipped into another place entirely. It can be jarring. Sentences become paragraphs and paragraphs become thickets of words when she lets them, because somehow, even when her sentences separate like the strands of a braid to the point at which you aren’t sure how exactly they ever came together in the first place, you never get the sense that she loses control. Mattia writes, “What happens once is in four dimensions. But whatever reverberates discovers another dimension, called ritual.” Her fiction weaves through the dimensions present in ordinary moments and draws unordinary moments into form, a bit like Samuel Delany’s behemoth Dhalgren. Like Delany in Dhalgren, Mattia carves out shoulders of The Fifth Wound’s page for more thoughts, what would otherwise be foot- or endnotes, sometimes an apostrophe or a memory. (I note with great joy that the person who introduced me to Dhalgren is Abbie Phelps, who designed and typeset the interior of Unsex Me Here and also designed and typeset the interior of Homodoxy’s first book.)

Her words crack open under the strain of mediating the divine, creating a dialect of her own.

Mattia repeats words frequently, and that repetition is the germ of this essay. As I read The Fifth Wound and Unsex Me Here, the repetition of certain, often unusual, words across stories and books began to irritate me—first, irritate as in slightly annoy; then, it felt like walking on a beach and noticing that my shoes (dumb bitch, I didn’t bring sandals) are slowly filling up with sand. Irritation as in noticing something unexpected is interrupting an experience that would otherwise be settling. What initially felt to me like a writer’s crutch became a reader’s hairshirt, scratches in the normal telling me to pay more attention because something is coming. Then, realizing I have my own words, I started typing this.

I started keeping a list of Mattian words after reading The Fifth Wound, partway through Unsex Me Here. I hadn’t yet read the part of the story “Celebrity Skin,” a mythology of transfemininity, in which the protagonist, Hylonome, discovers a miracle: a cult of women like her who worship a goddess like her, Aphroditos. Aphroditos is Aphrodite’s twin sister with “tumbling curls and full breasts” and beneath her gown, “a hard cock.” The Daughters of Aphroditos are similarly endowed fairy women, who take care of each other, teach each other how to be, have sex, and together, blossom in beauty.

One of the Daughters of Aphroditos, Ourania (born, yes, on Lesbos), is an oracle—the Daughters’ prophet. Ourania channels Aphroditos, delivering strange messages from the goddesshead while attempting to interpret them to the Daughters. She is a theologian and theorist who polishes her words. A Daughter says of her, “‘Certain words whirl around her mind for months, unnoticed until they begin to glint, to evince an iridescence, taking on, at last, a kind of substance, something like a premonition of life, the first thought of a world.’” The word Ourania is currently seeking to clarify is “Hermaphroiesis.” Ourania attempts to define it in a prophesy witnessed by Hylonome, but speaking is difficult for her. Her words crack open under the strain of mediating the divine, creating a dialect of her own.

The goddess who possesses her, Ourania says mid-channel,

splitten mi saintdances assunder wi’ babelon brewks of nonessense, overspellin’ mi lyk wyves o’ creamsin sheefome, blottee whatere amixin wit ruddee baubbles o’ vaporessense, spellin ope thru th’ rivt, floawing dawn lyk mourneighing mizt, replaysing whord wi’ blod ween mi voyce feyelles—chreu veintrille-o-chasm!

She asks the Daughters, “Dew yyu ciy wut hy’ceenth? A barockly decreat’d cavyearn, torcht by howlee efflame? Wails o’rawk poolsating wi th’ miserious, effeminaming heartbeast o’thee goldiss hersalve? . . . . Is yore fathe sophishn’t?” She arrives at “Hermaphroiesis” as if it is an arrival, but the word refuses to make sense. The prophesy maintains its opacity; she is not an expository preacher. Later, in the void that follows the hyperpresence of the prophetic moment, Ourania seems to admit defeat. The story’s narrator says, “‘Hermaphroiesis’ was, like so many divine proclamations, more thunder than lightning.” Something about this particular word felt “not only mysterious, not only muddy, but somehow corrupted”—and she can’t quite tell why.

Ourania’s shibboleth “Hermaphroiesis” is a joining of “hermaphrodite,” a word for bi-sexed beings, and perhaps “poiesis,” the poet’s act of creating and naming, an act irreducible to literal naming. Its refusal of definition is important, I think. It doesn’t define but illustrates and enacts. In it, two parts (hermaphrodite in that sense) become one in an act of poeisis. It can be used as a cipher for the oracle’s dialect.

In written form, Ourania’s speech fractures at almost every word. “Sentence” becomes “saint dance.” “Asunder” becomes “ass under.” “Crimson,” “cream sin.” “Replacing,” “replay sing.” “Sufficient,” “soph-ish n’t.” “I see, “hyacinth.” “Decorated,” “decreated.” The batshit brilliant thing is that all of these de- and recreated words have their own slippery logic. Sentences are where saints dance, which may or may not offer insight into how to read some of Mattia’s more difficult long sentences. Where is one torn asunder if not in the ass, under someone? Is your faith sufficient, or is it pretending to wisdom, soph-ish… n’t? The color of blood, crimson, becomes a kenning for the book’s other vital liquid, cream sin, cum. I see becomes a flower. What can be decorated can be decreated—artifice. The words slip out of your hands if you grip too tightly, and these readings last as long as you can hold them.

Ourania’s speech is Mattia’s attention to language condensed and radicalized. It hypostasizes Mattia’s pursuit of the ineffable into the unit of the word.

Some of Mattia’s resonant words: confection, myth, peach, powder, iridescent, pearlescent, opalescent, mother-of-pearl, diaphanous, perfume, angel, seafoam, and (wonderfully) aurora. The words that reoccur are, almost without fail, testaments to sensuous intermediary states, and if not that, names of colors (but never primaries). Mattia’s diction is trained on surfaces and the shifting dimensions and textures within them.

Mattia’s cultivated extravagance is not an aesthetic of high camp, then, but an asceticism of high cunt…

If the words are extravagant and queer, Mattia’s use of them is not camp but something beyond. There is a specific discipline to it. Her repetition is an ascetic practice, a shaping of her stories and herself through almost unflinching attention to the movements present within our smallest units of language. I said hairshirt; in “Madonna Della Nulla,” Peach chooses, instead, a corset. “Her corset was her cross. It helped her not to want too much; reminded her that passion was not an idea, it was an object you carried.” Tightening the laces does not satisfy the need but focuses it—“it [her need] was carved out by the curve of the corset, replaced by the force of whatever wasn’t , hadn’t been, before anything was. The same force that once kept the universe pressed into a point.” The corset is the pressure of the “never here,” which is Peach’s name for God. “As long as she wore the corset, God was bound to her. God was in the laces.”

I’m not a leatherman, but I feel something similar when I wear a leather harness (and to a more minor extent, a fanny pack). The constraint focuses my attention on my body’s inherent boundedness while simultaneously freeing me to move as if I love my already bounded body and believe others might want to love it, too. The motion is inward and outward at the same time. God is there, in the buckles as well as the laces, lovingly holding her queer creations together.

Mattia’s cultivated extravagance is not an aesthetic of high camp, then, but an asceticism of high cunt—so high, it requires contemplation—in which words and syntax tremble before their impossible task: naming the passions of the body outside the linguistic confines of an empire that the cries out for the crucifixion of queer people like a lepidopterist dreaming of a drawer filled with butterflies.

In an interview with Jordan Cutler-Tietjen printed in Unsex Me Here, Mattia speaks of her Christian upbringing, particularly of the instilling of trinitarian theology within her mind, as a “Trojan horse for an ethics of self-surveillance” and the god of American empire. Nevertheless, her writing is redolent with the sort of incarnation, sacrament, immanence and transcendence, creedal echoes, and mysticism that scholars of religion and literature continually study in the same five or six canonical twentieth-century writers. The Fifth Wound and Unsex Me Here should be taught in religion and literature courses, where they will singe their neighbors on the syllabus and confound seminar discussions in good ways. They would also find a home in a queer theology classroom.

I have much more to say about these two books—they deserve more, so maybe I’ll write a substantial essay on them eventually—but I am once again late in sending this out and have other reading and writing I have to do. I haven’t really given an account of either book, but my reviews are never really reviews. Oops! Read the books and tell me what you think.

I’d like to briefly add that Unsex Me Here was slated to be published by Coffee House Press, but after the Press ignored a statement of almost seventy of its writers calling for the press to endorse the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI), Mattia pulled it, and Nightboat, which published her first book, published it. Mattia’s writing is one piece of evidence that the artist can be both devoted to craft and courageous, and I am grateful to her for that. And grateful to Nightboat for publishing good, sometimes difficult queer writing.

May all our gardens bloom. Happy Easter.

<3,

sam