in the dark

unseen

until it is too late to stop

that is how the seeds grow

– Jesus, in Dayspring by Anthony Oliveira

I drove to the monastery. I had missed my graduate class’s annual trip, a requirement for the certificate in Anglican Studies, so I had to take a private retreat. Even though it was required, I’d been looking forward to it. My thoughts were scattered. I once felt a clear calling to ordained ministry, and I wasn’t sure if I still had it.

I don’t think of my time in divinity school as particularly harrowing, but my journals suggest that I was often overwhelmed by coursework and deeply distressed about sex and sexuality. My partners shifted from a couple of short relationships to more casual encounters facilitated through hookup apps. My body was calling me to others and was calling others to me in ways that felt both fulfilling and anxiety inducing. Fulfilling because my body was created to attend and be attended to, and sexual attention rooted me into myself in a way I hadn’t experienced before. Anxiety inducing because I had turned body hatred into a spiritual practice. An attempted disavowal of the meat of me had become a core element of my relationship with God. Putting myself out there was also anxiety inducing because, as I stepped into the world of gay social and sexual life, I had new expectations and identities to sift through. Sexual encounters and wardrobe changes entailed the discernment of spirits. I thought this parsing of desire was only groundwork for whatever formal discernment awaited me, but parsing desire itself became my calling.

How could an icon touch me in ways a lover can’t? The image of God is in every person. Is my desire too literal?

It felt a lot like flailing in a lake, and the spiritual director assigned to me for the retreat was intent on dragging me to dry ground. The Brother was probably ten years older than I was, and as a fellow gay man, he thought he saw himself in me. He told me I was using sex in order to run from God, which was resulting in a splitting of sexuality from faith. I knew that was not true—the garment was already rent, or I never had it. I had bought an icon of Jesus the Bridegroom, nymphios in Greek, at the Brothers’ gift shop. I showed it to my spiritual director, who admired it and told me to return to my cell and meditate on the icon. In gazing at the beautiful body of Jesus, my faith and desires would knit themselves back together.

The icon is beautiful. Even erotic. A bearded Jesus carries a thin rod. He looks down at it demurely, and you notice his hands are tied with rope. He wears a crown of thorns, and he is robed in a soft lavender. The robe doesn’t cover his breast and side, soon to be pierced with a spear. I stared at it (not just his nipple but the whole icon and also his nipple) not knowing what to do or expect. I wondered if I was supposed to be getting aroused. Jerking off seemed crude and would have felt more like an imposition than a flowering of whatever latent holiness was supposed to flower within me. How could this image touch my hunger in the way my spiritual director seemed to think it could? How could an icon touch me in ways a lover can’t? The image of God is in every person. Is my desire too literal?

I took my glasses off to let my vision relax. The icon’s features shifted and softened. Instead of coaxing out of me some new desire for God, the attractive bound Christ turned before me into a drag queen. I spent the rest of my meditation time writing a goofy poem about Jesus Christ, the glamazon. The Brother’s exercise didn’t work the way he wanted. I don’t remember if he was amused or annoyed at our follow up session.

For many gay men raised in churches, particularly Catholic churches but any setting in which a beautiful Christ is hung on a cross or in a frame, images of Jesus are inaugurators of sexual awareness. Wrestling with the Angel: Faith and Religion in the Lives of Gay Men, an essay collection published in 1995, contains a couple examples of this.

Don Belton writes about the images of Christ as “a beautiful young white man” in his childhood home. In Belton’s neighborhood, Black and white people did not associate. The white men on the television and in town were ungovernable and dangerous—“worse than the Devil, because, according to my father’s religion, the Devil had been put under the subjection of God,” while the white man was subject to no one. It was odd to have a white Jesus in his Black Sanctified Holiness house. The presence of a such a god “was a sign of ambiguity in a house where everything else seemed hard and fast.” Beauty was part of Jesus’s strangeness. In his father’s images of Christ, there was a “clear association of maleness with beauty.” As in my icon, “scant, diaphanous clothes. . . parted strategically to provide voyeuristic focus on beautiful limbs, a naked heart.” Belton writes, “The only thing I had to compare these pictures to back then was the provocative. . . pinup girl calendar photos hanging in the office of an uncle’s gas station and the neighborhood barber shop.” Dad had Jesus; uncle had pinups. What would Don have? The images of Jesus were signs of some sort of erotic beyond within, clearly different from the rest of their home’s décor but placed meticulously by his father as if their inclusion made sense.

In Andrew Holleran’s essay for the volume, he recalls how, in an earlier Catholic part of his life, “Christian imagery and homosexual life mingled; it was all a celebration of the male form. The lean man lying in his room at the baths, feet-first toward the hallway, resembled exactly Mantegna’s painting of Christ descended from the Cross. The magic of his embrace was the same ecstasy Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross described in their meditations on Christ the Bridegroom.” Holleran illustrates how images of Christ teach young gay men how to embrace a male body not only with tenderness but with pleasure. They prime one to see the holiness in one’s desire and in sexual scenes one may encounter.

I have never lusted after Jesus. I was raised a pietist Protestant: our crosses were bare. Jesus had risen—maybe that’s why I didn’t know which bodies to long for. I don’t recall other images of Jesus hanging about the churches we attended or the churches where my mother, a pastor, preached. Our denomination was the Covenant Church, a Swedish import to the United States. When visiting other Covenant churches on vacation, it was not uncommon to see the Head of Christ by the Swedish painter Warner Sallman, one of the more prominent iterations of tanned white Jesus with luscious hair, hanging in the narthex of the odd hallway. You’ll recognize it if you search for it. My churches were predominantly white, and the rare image of Jesus I saw was white and typically clothed—his presence didn’t point to much. If they taught me anything, they taught me the aesthetics of Christian kitsch. When I did see a Jesus stripped on the cross, probably at the Catholic elementary school I attended, my primary thought was that it must have been a shitty way to die. It ended there. The crucifixion did not point me to other men. But I found them eventually.

There is a genre of writing that reimagines stories from the bible, piecing together scripture’s narrative fragments into portraits of particular figures or providing interiority to people who only appear as blips in the canon. I think of poems by my friend Megan McDermott, a queer Episcopal priest, and Tania Runyan’s collection A Thousand Vessels. My mother writes occasionally in this vein, also. Recent examples of novels like this include Naomi Alderman’s The Liars’ Gospel, Mary Rakow’s This Is Why I Came, and Colm Tóibín’s The Testament of Mary. I pull The Testament of Mary off the shelf.

For some, Mary is an icon of assent to an inscrutable divine will or, in her deliverance of the incarnate Good News to the world, the prototypical priest. Tóibín’s Mary is the proto-skeptic, a brilliant and wary observer of a disturbing phenomenon bubbling up around her own family. Mary watches with unease and disdain as her son gains a following: “Something about the earnestness of those young men repelled me, sent me into the kitchen, or the garden; something of their awkward hunger, or the sense that there was something missing in each one of them, made me want to serve the food, or water, or whatever, and then disappear before I had heard a single word of what they were talking about. . . . there were too many of them talking at the same time, or even worse, when my son would insist on silence and begin to address them as though they were a crowd, his voice all false, and his tone all stilted, and I could not bear to hear him.” The men have “elaborate… desires,” and Mary sees “brutality boiling in their blood.” Mary is intelligent and watchful, but she is also being watched by her son’s friends. She is under their care, like one might be under the care of, and wary of, the local mafia.

After Mary’s son (she cannot speak his name without breaking something in her) is crucified, she is visited by a couple of her son’s friends, including one she calls “the guardian,” perhaps Tóibín’s replacement for the Beloved Disciple. The two control her life, re-arrange the furniture in her home as if it was their own. Mary hates these intruders, and at one point threatens them with a knife. They ask her to repeat what she saw of her son’s life and death, ignoring her love of small details, downplaying perplexity, pushing for simplicity.

Mary has dreams of her son in which she and the Mary Magdalene, her friend, take care of his broken body. The two women share a dream. In the dream, they are woken from sleep by an appearance of Mary’s son, alive again, in the house where they take shelter. Hearing the women discuss their shared dream, one of Mary’s watchers smiles and says “that he had always known that this would happen, that it was part of what had been foretold,” and makes the two women repeat it many times. The guardian and the other man begin to form their own narratives of him, taxidermizing the corpse of Mary’s son with bloated ideas of eternity, explaining to her “what had happened to me at my son’s conception,” how he died to redeem the world, his necessary suffering, eternal life, making “simple sense of things which are not simple.”

Mary’s anger mounts as the men turn her son into something he was not: the Son of God. Watching hungry interpretation congeal into narrative and canon before her own eyes, Mary interrupts, saying, “I was there… I fled before it was over, but if you want witnesses then I am one and I can tell you now, when you say that he redeemed the world, I will say that it was not worth it. It was not worth it.” Tóibín names Mary’s story a testament, not a gospel, and this is significant: what Mary witnessed is not good news. Turning a man into a god requires a sacrifice. The cost is Mary’s own careful memory and interpretation. The cost is her son.

Tóibín is not trying to feed a god to the hungry.

I want to have Mary’s eyes and mind, but I have the deranged hunger of a disciple. I try, in my hunger, to let things be what they are, to hope for the most of them; that is, I wouldn’t want to be one of Jesus’s friends in The Testament of Mary. In some of the people I admire most, I see both hunger and intellect feeding each other, heightening one another, like lovers. The challenge of The Testament of Mary is in the splitting of the two. The disciples’ cruel hunger and Mary’s cold intelligence make Mary and the friends of her son both feel less real, less true, less human. They are glitteringly rendered types of familiar characters from apologetic literature: the stupid, dangerous believer, the complex doubter.

This Mary is not so “convincing” that it has “forever transformed” how I understand the mother of the Son of God (I quote the marketing copy on the book’s back cover). Queer, feminist, and womanist theologians have long warned against turning Mary into an unthinking reproductive function or a model of compulsory virginity. I already understood her to be a complex figure—an intelligent thinker, a theologian, and a young woman with an impossible relationship with God. I am not convinced, though, that the book wants to be convincing as much as it wants to demonstrate the cost of conviction and the danger of hungers that reach for conviction like a drowning person reaching for a life raft or some behemoth tentacle angling for a foot. All the same, I would prefer to learn from one who has been gripped and flails in the deep than one watching from the shore, whose knowledge requires distance.

What makes the book unsatisfying to me is also what makes it valuable as its own project, separate from what I want from the gospels: Tóibín is not trying to feed a god to the hungry. The telling is his own. And the resulting text is at times frighteningly real. His hunt for humanity in the gospels produced a retelling of Lazarus’s awakening that has changed how I read that story—the dead man shrieking as he returns to life.

I am not yet sure how to describe adequately the distinction between writing from within my own hunger and writing about another’s hunger, as if beyond it. It cuts both ways. Both have their dangers, their types, their false and easy wisdoms.

In a very short sermon for morning prayer at my divinity school, the playwright and priest Mark Schultz preached on a passage in which Jesus calls his first disciples, probably Matthew 4:18 – 22. Jesus approaches two brothers fishing, says, “Follow me, and I will make you fish for people.” Immediately, they drop their nets to follow. He sees two other brothers mending their nets and calls on them, as well. They, too, immediately follow.

Why do the two pairs of brothers follow this man? No explanation is given. The narrative moves too quickly for motive. In other sermons I’ve heard on the passage, the disciples were said to be dissatisfied with their lives, bored, stalled, waiting for purpose—you know, like you are, is the implication—and Jesus had something like a compelling air of purpose. Or, maybe there was more to these interactions than what Matthew recorded. Jesus’s invitation was thorough and reasoned. They had a conversation. He sold them on a vision.

Allowing the text’s sparseness to speak, Fr. Mark suggested that Jesus was so dazzlingly beautiful that, upon seeing him, the disciples wanted to be near him. The interpretation is so minimal, so unimposing. Fr. Mark didn’t speculate about orientations or identities or sexual activity unfit to include in the official version, nor did he speculate about the fishermen’s dissatisfaction with their careers. I could see myself in these disciples. I’m not sure what this says about me, but there are men for whom I’ve wanted to, for whom I would, drop everything.

I arrive at the impetus for this essay, the text that provoked the above thoughts, which I hope provide an adequate nest for it.

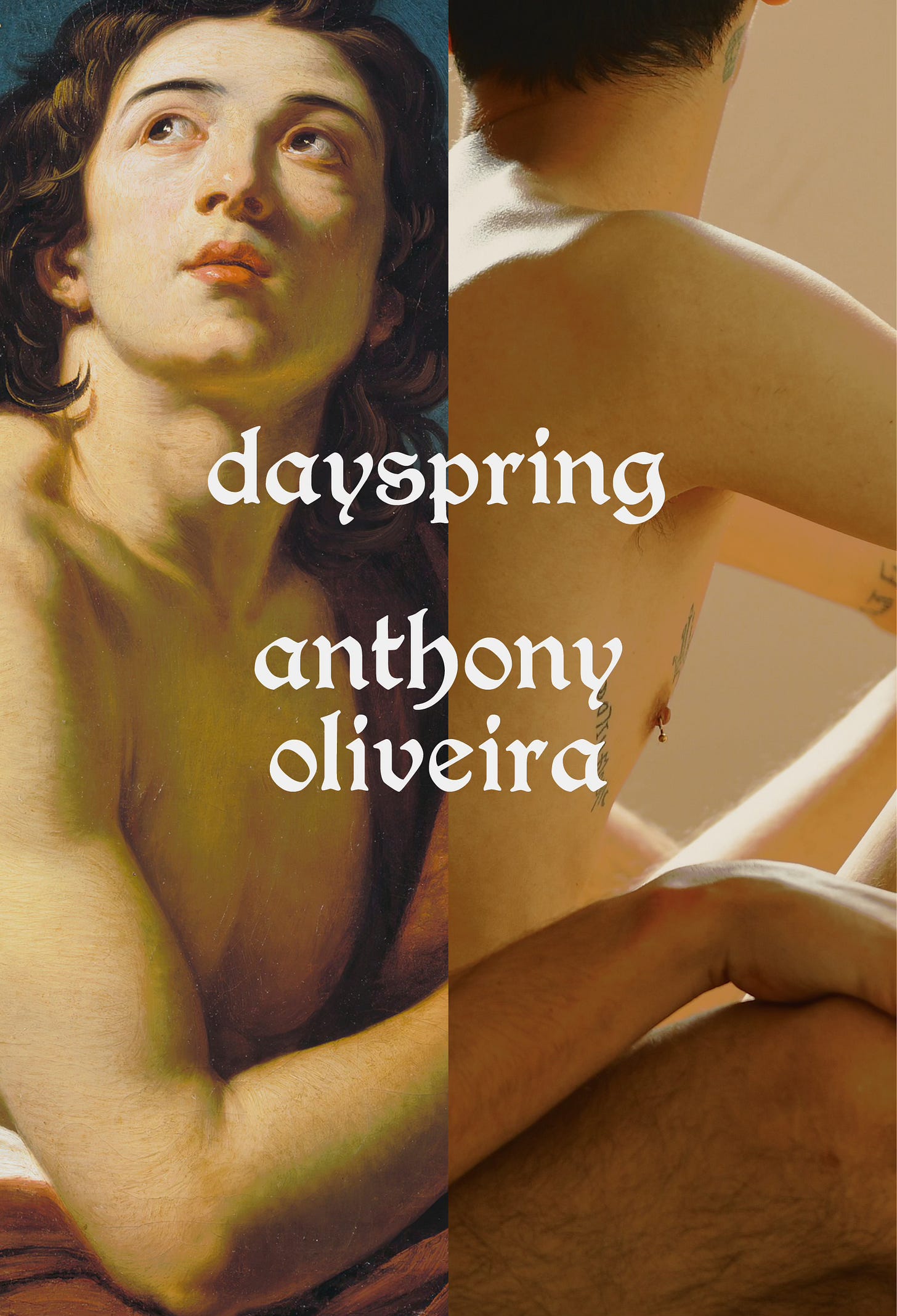

Anthony Oliveira’s new book, Dayspring, tells the relationship between Jesus and the Beloved Disciple, John, as one of desire, love, and sex. The Son of God incarnates as a sweet and impish fag with apocalyptic wisdom, a sense of humor, a sometimes pimpled ass, and a sexual hunger that befits this iteration of Jesus.

The two boys meet at school, with Jesus nestling up against John in a little nook to say, “hi! what are you reading?” before swiping John’s comic book. Later, John recalls Jesus holding him “in the dark, with the DVD menu looping. . . and kissed a zigzag constellation down the meridian of my face. . . . like the coal the angel pressed to Isaiah’s mouth / and you became my faith.” When one’s lover is the Son of God, is there a distinction between faith and desire? Is there ever such a distinction?

For some, Dayspring will serve as an unusual introductory survey in Christian theology, and I envy those readers.

The text offered as Dayspring is assembled by John after the death of Jesus. John is tasked with writing something about his lover that will last. The text, then, ought to be read as composed not only by Oliveira but by John, who is piecing together fragments of stories and quotations in hopes of remembering and sharing his beloved. On the book’s title page, below the title, a list appears suggesting that John’s hand has produced a prismatic text:

the disciple whom he loved

neaniskos*

notes towards a revelation

the young man in white

a chapbook

a theophany^

a gospel

a great blasphemy

against the heretic cerinthus~

a breviary

a hymnal

a memoir

a work of plagiarism

an account of the word made flesh

Notes from Sam:

* a youth or young man

^ a tangible encounter with God, like Moses’s burning bush

~ according to Irenaeus’s Against Heresies, Cerinthus was an Egyptian who taught that the world was created by a power separate from God and that Jesus’s birth was of the normal type, not of the Holy Spirit

A couple pages into the book, John records, “there was a word / i echo.” This is a remarkable condensation of the polyphony to come into the briefest of testimonies.

Dayspring is highly fragmented. It is structured in short lengths of text—scenes, memories, borrowings—that are stylized on the page in variously indented lines and paragraphs of various lengths. As a gospel, Dayspring tells the life of Christ. And, as in some printings of the gospel, the words of Jesus appear in red ink. It is a gorgeously designed book, and I was shocked when my review copy came signed, with a sketch of a burning sacred heart on the title page in red and black ink.

Amidst the scenes of Jesus and John, the Beloved Disciple places passages of psalms, biblical prophecies, mystical texts, and theology. Some of them, one might expect, like visions of Saint Teresa of Avila and Julian of Norwich, poems by Herbert and Donne, snippets of Augustine. I was not expecting to find G. K. Chesterton on wonder, a prayer of penance from the Book of Common Prayer (in the old language of Rite I for you liturgy queens), Jean Calvin on self-denial from Institutes 3.7.1, Sojourner Truth’s encounter with the bigness of God, even a meditation on Jesus’s side wound from the pretty niche Nikolaus von Zinzendorf, a spiritual forebear of my own and other pietist sects. For some, Dayspring will serve as an unusual introductory survey in Christian theology, and I envy those readers.

If you want, you can find a roughly chronological trajectory within the book, with some beginnings at the beginning (an excerpt of the Gospel of John’s creation story and a telling or two of the Beloved Disciple’s invitation to discipleship) and some endings at the end (Jesus’s resurrection and a tender goodbye between Jesus and the Beloved Disciple). But there are also endings at the beginning and beginnings at the end and both throughout. The Apocalypse of John at Patmos, the final book of the Christian bible, unfolds slowly across the fragments. Time collapses. The Roman empire is a looming threat, and the Cathedral of Notre Dame is burning.

Jesus paraphrases his words in the canonical gospels, offering variations and fantasias on his teachings and parables. These may arrive as a familiar gospel scene unfolds (like Jesus’s baptism, the wedding at Cana, or the last supper). They may be massaged into an encounter between Jesus and John. Or, they may be found sitting nakedly on a page of their own: red words delicately placed on cream-white paper, like a ruby bracelet pooled in a box lined with satin.

Some of Jesus’s aphorisms adhere closely to their biblical antecedents while others veer off freely. A sampling:

“there is no greater love than this: / to lay down your life / for your friend”

“somewhere / even the hairs of your head / have been counted”

“don’t pray in public / those that do / have already got what they wanted out of it / and it had nothing to do with god”

“to follow me is to /set your teeth / upon the curb”

“to be rich / is to be damned”

Like their biblical referents when read out of context, one or two of Jesus’s sayings in Dayspring can sound like inspirational wall art. Initially, I rolled my eyes at a couple, like “be the light / however vast the dark.” But why not? This Jesus is a youthful gay who toggles between telling goofy stories to his lover and issuing warnings about the end of the world, who conjures booze for a wedding party (“ah fuck it let’s do a miracle”) and curses a fig tree (“just absolutely screamed at it for / like forty-five minutes”). He is tender; he is angry. He giveth and taketh away. These tonal modulations make a certain sense when Christ is a chaotic twink.

In addition to materials from the Christian gospels, John picks up biblical stories like the love between David and Jonathan from 1 Samuel. For many gays, it is a story that provides a biblical precedent for gay love, and numerous gay marriage rites include verses about them. In Dayspring, Jonathan’s love for David, which famously surpassethed the love of women, is noticed by Jonathan’s father, King Saul. Saul is ashamed of his son, “the son who should have been his staff / now bent to chew his pillow and sheets in the rank / sweat of an ensemened bed // jonathan who is the prince-punk of a shepherd / sodomized still stinking of the lambs.” Saul’s shame mirrors another passage I cite below in which Jesus and the Beloved Disciple are discovered. Christians love typologies, and in the juxtaposition of his own love with that between Jonathan and David, one can see John, the Beloved Disciple, reaching for a parallel: Jonathan, the son of King Saul, and John the Beloved; King David and Jesus of the lineage of King David.

An explicitly queer rendering of David and Jonathan alerts some of my queer theological reservations. Who needs it, and why? Gay and trans Christians sometimes seek ancestors, prototypes. The hunt is often driven by self-defense: we belong here, look. We shelter ourselves in the bible from those who say the bible is only hostile to us. But this can also entail sheltering ourselves within inherited hermeneutical agendas that run deep in our reading of scripture, rather than asking if gay lives encountering scripture and God might result in new blessèd forms. So, we place the story of David and Jonathan in marriage rites.

Dayspring escapes the burden of necessity that yokes some popular versions of gay/queer biblical interpretation. Its purpose is not to argue for the legitimacy of gay relationships. Its audience is not primarily tolerant Christian heterosexuals and authority figures but queers and those who speak our language. Marriage is not on the table. The love and sex shared by John and Jesus are particular and intimate, but the specificity of their love does not limit their love for others. In their goodbye, John says, “I will never love anyone anything / like you the same again.” Jesus responds, “oh / no // never the same / never again / each time different / each wave still the sea / lathing bottlecaps and feathers / making all things old and new.” Yet still, “i am with you always / till the age’s end // it’s you and me handsome / only love / as i have loved you.” In loving Jesus, John learns to love others. The narrowing of desire onto the beloved refracts it outward.

Robert Glück shares a sentiment similar to this in About Ed (2024), his memoir about a relationship with a longtime lover who died of AIDS. I should really be referencing Glück here for his astounding and confounding novel Margery Kempe (1994), an account of the relationships between, on one hand, the English mystic Margery Kempe and Jesus, and on the other hand, the author and a lover. Margery Kempe is structured by Glück’s gamble that love of God and love of a man might in fact be the same love, or that one love might clarify the other. Margery’s pursuit of Jesus and Bob’s pursuit of his lover overlap, breaking in and out of each other as Bob and Margery both chase their beautiful, slippery beloveds and the narrative chases a similarly slippery alignment between loving God and loving a human. The novel asks on a formal level, if they are different loves, how they hold together. There is more to say about that another time.

In About Ed, too, desire compounds. Glück writes, “We didn’t know that our desire for each other included our longing for all men. I concentrate I start small a small piece of his skin. I didn’t know that giving him pleasure meant exciting all creation. I expand piece by piece and when I come I’ve created the universe.” In desiring Ed, Glück desires all men; in pleasuring each other, they pleasure everything. Both Glück and Oliveira name an exponential compounding of desire—a mutuality that multiplies, a fulfillment that is also a reaching out, like the faces of the blessed in Dante’s Paradiso reflecting an ever brightening light. That could also be one way of approaching the book’s fragments.

Gay vernacular is ever changing, ever borrowing and adapting language, and the Beloved Disciple speaks it fluently. One of his fragments refers to St. Sebastian as a “hot idiot twink go-go dancer pass-around party bottom of the lord pincushioned through with arrows.” There is a part of me, a tenderness, reserved for faggoty diction, flagrant flaunting of gay idioms, like those Oliveira strings together to mark the gay-claimed soldier martyr. Of course he wasn’t, and yes, that is exactly who St. Sebastian is. In the book, words like “sodomite” and “faggot” appear in the mouths of lovers and haters alike, calling to mind the The Queer God (2003) by queer Argentinian liberationist theologian Marcella Althaus-Reid, in which she offers “God the Sodomite” as a queer inculturation of the gospel, which, to be true, must be a category error.

The gospel’s gay language is lived in. It can be fun and flippant. It can be precise. John recalls a moment from their youth. John sat with Jesus on the futon in John’s basement watching TV. Jesus’s pants were unfastened, but that’s about it. He rested his head on John’s shoulder and “traced idle circles on the flannel of my shoulder.” John’s father walked down the stairs and froze while Jesus jumps up and buckles himself up. In that moment of recognition in which John’s father realizes the two friends are more than that, John recalls “i felt a white-hot brand press into my flesh and sputter there / / i was just your faggot now.” The two weren’t caught in any sexual act, but the suggestion of it is enough to mark John as an f-slur.

To be “just” someone’s faggot is to be fully dependent on them for one’s own pleasure, delighting in feeling weak or abject. In a recent episode of Sniffies’ Cruising Confessions on degradation, hosts Gabe Gonzalez and Chris Patterson-Rosso note that “faggot” isn’t a word all gays like to use generally or in sex, but some do, drawing its violent history into a space of erotic resignification. It is a scarlet letter, and as it happens, the words on the page following the basement scene are red: “be thou faithful unto death / and i will give thee a crown of life.” Faithfulness to Jesus makes John a faggot, and his desire makes him faithful to Jesus. His faith and desire are one.

The holiness of sex in Dayspring often enters through stigma, filth, and fluid. It isn’t dark—some of the text’s moments of abjection are glaringly bright, cleaving to a form of gay life that relishes the body’s theologically neglected gardens and streams.

After drinking beers at a bonfire, Jesus says, “hang on i gotta piss,” and pulls John into the dark woods, where John tastes the body of Jesus in one of its more humanly fragrant moments before Jesus pins and pierces him. In a textual fragment of apostrophe to Jesus, John meditates on an under-theologized element of the incarnation: Jesus’s miraculous spit. He writes, “your saliva has been as a charism / bringing hearing to the deaf and causing the blind to see / what then must it have done to me / hallowed in my whimpering / holy in my cries / as you spat to slicken my dilating pucker / your spittle dribbling down my haunch / preparing the way of the lord.” Saliva is a transformative agent. As it opens the eyes of the blind, it opens John’s ass.

You are blessed when you are reviled.

The “dilating pucker” brings us to the anus, which peeks out at various points in the book, putting Dayspring in conversation with the most explicit (and often most French) of gay theorists and writers. This includes Verlaine and Rimbaud, whose co-written “sonnet to the asshole” is reprinted on one of the Disciple’s pages: “mauve rosebud, a puckering gentle pink / an earthy twitch set in a humid loam.” Note the flowery imagery used to describe an organ not of procreation but of refusal and pleasure—a metaphor perhaps foreign, but familiar to any fister. The asshole is or may become like a rosebud. It is part of creation, worthy of the attention of a lover, a sinner, a disciple, a savior, as well as a writer, a theologian. In the incarnation, it, too, is inhabited flesh.

In Oliveira’s hands, scripture’s pericopes implode into pleasure, like Eugene Peterson’s The Message after a hit of poppers. The incarnation dilates. The canon softens.

A vision of new life emerges from the book’s jostling fragments. You can already see the shape of it in the way Jesus and his Beloved Disciple cherish their bodies’ hidden places. As Peter, filled with the Holy Spirit, testifies in Acts 4, “Jesus is ‘the stone that was rejected by you, the builders; it has become the cornerstone.” To Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, John adds a new beatitude, a “queer beatitude,” to use a phrase from a conversation between Garth Greenwell and Brandon Taylor. The beatitude might be something like the faggot shall inherit the crown of life. Or, to quote Althaus-Reid’s Queer God: “God’s love belongs to the Sodomite kind, for God’s love is not biologically procreative.” Or, to quote Jesus in Matthew 5 (NRSVue): “Blessed are you when people revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.” Or, to quote Oliveira’s Jesus: “if you are hated now / you will be adored.” The beatitudes are apocalyptic blessings whose utterance collapses the future and the present, making the distance we, as time-bound creatures, experience between now and then intolerable. But, counterintuitively, the promises of a good future collide with present debasements. You are blessed when you are reviled.

Oliveira’s inversion of the body’s more vilified parts and functions resonates with writing by Guy Hocquenghem, Leo Bersani (who is briefly referenced in Dayspring), and Darieck Scott, who find in abjection and the anus an organ for variously rethinking self, society, Blackness, and family. If I had more time to flesh out these connections, I might, but I am already running long. Happily, it is a strand in queer theory (often termed “queer negativity”) that is already being brought into theology and biblical studies by Linn Marie Tonstad, Rhiannon Graybill, Brandy Daniels, Kent Brintnall, Max Thornton, and others. Most recently, see Lee Edelman and the Queer Study of Religion (2024), edited by Brintnall, Tonstad, and Graybill. (I currently have institutional access to it, so if there are particular chapters you would like emailed to you, reach out at mr@homodoxy.com.)

I imagine the Beloved Disciple sitting in his room with a mountain of paper scraps, assembling the leaves and reassembling them, unsure of how best to witness to his beloved, wondering how a book could ever take the place of a body. I’m glad for his work, because, although I never wanted a gay Jesus, I’m glad I have him. I see bits of my own lovers in him.

I recall a call I once had a with a priest friend when a lover was having some serious difficulties. The priest told me that my love for my lover was God’s love for him, and his love for me was God’s love for me. It was necessary to hear. I am so cautious about not deifying whatever and whomever I love or desire that I sometimes miss the ways God may draw me deeper in. The Beloved Disciple isn’t the exception but the paradigm.

Dayspring offers scraps of kataphatic theology for catamites. It has been a wonderful text for the first missive from The Rearview, and I’m grateful that it has provoked me to think about Jesus in ways that speak to and from my desire. A huge thank you to Anthony Oliveira and Strange Light for the signed copy.

Future dispatches from The Rearview will feature more reviews, interviews, and views, primarily from me, but from friends, too. I hope this Substack will help flesh out a vision for Homodoxy and the kind of books it will seek to publish. Please follow along and share it with friends who might be interested.

Thank you for reading.

Gaily yours,

Sam

edit 9/24: a couple of typos